What happens after impact?

The real test for empathy.

Some months have passed since I completed the ‘Re-imagining Islam’ public engagement project. It ran from autumn 2015 through to summer 2019, drew in several rounds of finance from my native Warwick University and later external funders such as Arts Council England. It was a huge undertaking for all involved.

As the UK’s Research Excellence Framework (REF) requires, over recent months my home institution has been feverishly engaged in writing up an effective ‘impact case study’ with me. This involves showing whom the work has benefited, which communities, groups, constituencies and institutions have gained as a result, what they have gained, and what evidence there is for these claims. It’s become a core area of activity for academia in the UK, and most universities are throwing considerable resources at it.

As I consider my project with a certain distance, actually from a period of leave in Melbourne Australia, it’s obvious how the work sparked a transformative learning process for all involved, and not least for me. It has altered not only how I approach working with non-academic communities, but also how I write as a researcher. And in a quite profound way it has altered me personally, so much so that the proverbial ‘journey’ has been mentioned on more than one occasion. Except that this isn’t and shouldn’t be a story about me, or academics like me, though at times it threatens to become one.

I actually wonder if the very process of critical reflection, driven by the REF impact agenda and its case-studies, lies at the root of this. There’s a certain self-reflexive aspect to writing about the so-called ‘impact’ academics have. Of course, it’s almost inevitable as we try to evaluate what we have achieved. The problem is, though, that although public engagement is designed to benefit the non-academic world, the writing-up process that follows shines the light back on to the academy, tempting universities to pat themselves on the back and tell stories about how they are ‘reaching out’ and ‘making a difference’. This can also boost the careers, profiles and self-esteem of academics like me, who get to show just how 'woke' they really are. Much of this good news may be true, but what happens to the relationships supposedly forged between us as researchers and our beneficiaries once our collaborative projects expire? What happens, in other words, after impact?

Working with the Soul City Arts community arts collective in Birmingham during the final year of my project, I doubtless benefitted from the project planning, liaison and production skills of producers like Steven McLean and Abigail Shervington. They introduced me to Mohsen Keiany, a British-Iranian painter who was already working through his own childhood experiences of the de-humanisation of war through a cycle of disturbing oil-on-canvas paintings. Responding to the powerful image of the two chairs in Weimar, written about in these blogs at length and introduced to him through our dialogue, Keiany envisaged a brief empathetic encounter, again symbolised by two chairs set atop the ruins of war, and the work ‘Meeting Point’ was born (see below). Sound artist Matt Parker then made field recordings of the bells form local churches and arranged these into a multi-channel installation, entitled ‘These Times,’ which built in complexity and gave sound both to the ticking bombs and the psychological time-bomb of PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) treated in Keiany’s paintings.

Yet how would these works fit together, connect with communities and bring benefit to them? The production team helped familiarise both artists with my work and had begun making connections between them. Most significantly, though, they introduced me to urban artist, curator and educator Mohammed Ali. Ali helped the project in both methodological and artistic terms. He wove together a cohesive narrative for the project as whole. He also brought communities in to engage with the art, not least by creating immersive engagement and encounter spaces in diverse and often unconventional urban locations. Finally, he helped to foreground a theme the producers and I had identified as core to my research and of importance to participating communities: that of empathy.

Over a two-year period, we ran a programme of engagement activities, including one of Soul City’s tried and tested ‘Hubb Debates’, which combined atmospheric lighting and sound in an intimate space with topical discussion. Our topic was on the rebirth of ‘race hatred’ in society and media and the supposed demise of empathy. The voices of community members, recounting their experiences, were recorded and fed into the archives from which Ali would build his work. We engaged with schools, recording pupil’s voices as they spoke of their experiences around (often the breakdown) of interpersonal and cross-community empathy. Ali also visited communities traumatised by the Bosnian genocide in Srebrenica, recording interviews with victims and witnesses alike.

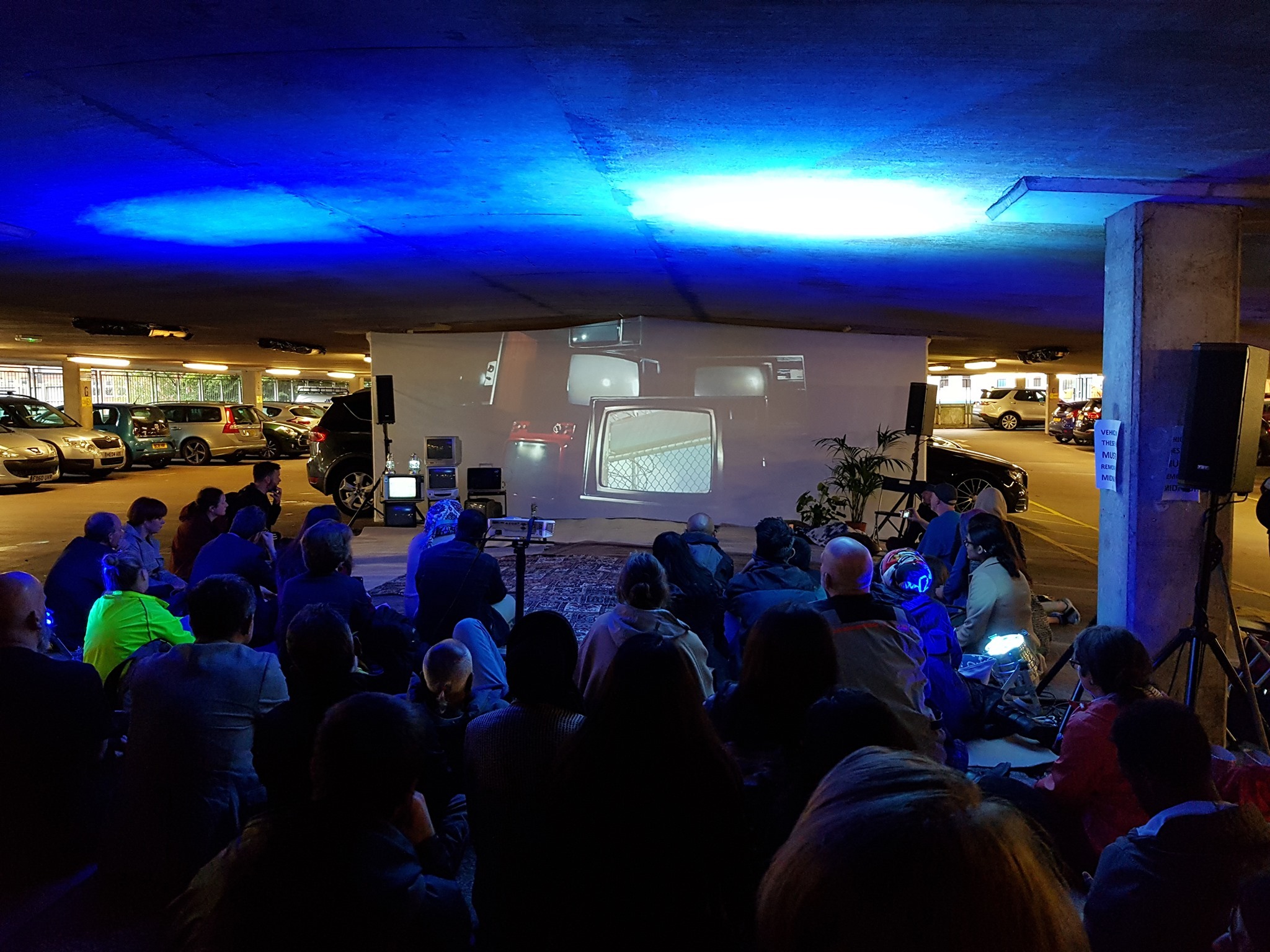

Ali’s short film Art of Empathy drew together this material and formed the centre piece of the events we ran during summer 2019. We took over St Michael’s house, an outreach ministry of Coventry Cathedral, installing Parker’s sound art in the space outside the house, placing images of Keiany’s exhibitions in one room and screening Ali’s film in another – a long-table discussion followed on the themes dealt with. A month later, we used the paintings, the film and sound installation to take over and transform one floor of a multi-storey carpark in central Birmingham, drawing in not only established arts crowds but also passing commuters, young people and the wider public generally. The US/Tunisian based futurist thinker and storyteller Mark Gonzales led a workshop that drew people together in discussion, drawing off the artworks and converging on the theme of empathy one final time.

The whole season of activities produced an abundance of data. This comprised both quantitative, statistical records of footfall and demographic diversity. It also included qualitative material, such as voice recordings and written testimonials. These testified to participants' views on the importance of the theme and also their surprise at how transformative this encounter with the arts had been as it spawned new and unexpected relationships across communities. As a public engagement exercise this was doubtless a success.

Looking back, though, a true measure of the project’s success lies not so much in my case study and how well it will be received by my peers. It lies in the fact that relationships forged have continued to endure and grow. The communities engaged are still my partners, and I am still working with Ali to fund a visit to Australia during 2020 to work on public art installations based on Muslim prayer. In measurable, professional terms this work gains me nothing, and neither is just a sneaky way of popping a different kind of worthy feather in my cap. The work flows rather from our shared convictions on the importance of empathy and is a natural continuation of the theme we worked on and the method of working we developed together. In a roundabout way, it is this ongoing work that is the true legacy. It is, though, something that will not be written about in any case study, or probably anywhere outside these pages. It testifies to a lasting impact, or maybe a kind of impact after the event. And, happily enough, it ticks no official boxes and cannot and need not be measured.

a UK academic exploring Islam through global history and culture.